Your sperm is your future

As seen in

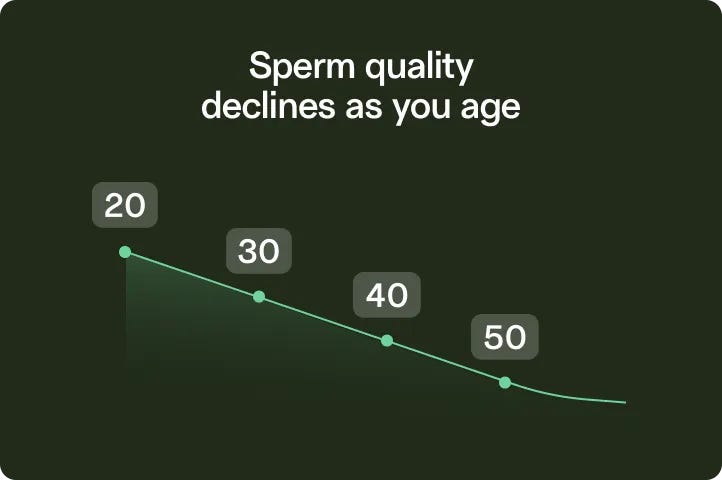

Fertility declines with each birthday

Past 35, you’re more likely to deal with infertility — and your child has a higher risk of conditions like autism.

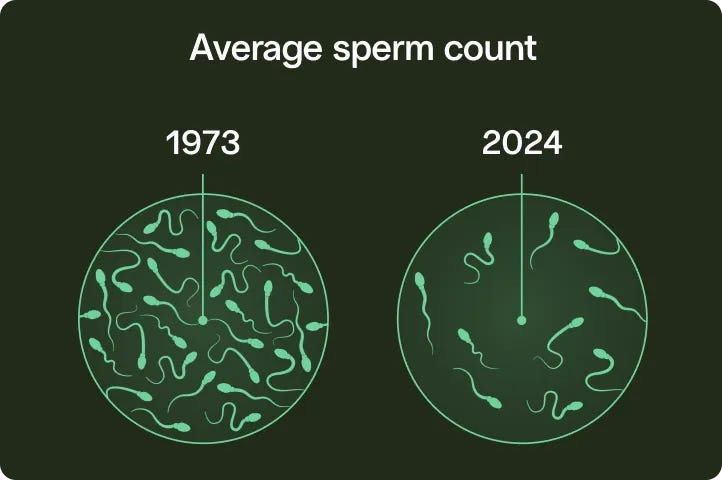

Our sperm is not okay

Sperm counts have dropped over 50% since the 1970s, thanks to chemicals, plastics, and our modern lifestyles.

Clinics are awkward and expensive

With the old-school approach, you wait months for an appointment in the communal “collection room” (yikes).

Test your sperm. Preserve it at its peak. Without leaving home.

Get started

From checkout to lab in less than a week

10x faster than a traditional clinic. Get the data you need to get pregnant faster, faster — or freeze your sperm without delaying upcoming medical treatments.

Save over 60% compared to clinics

We’re making future family planning an option for all. Sperm freezing starts at $145 per year, and we’re in network with most major insurance plans and benefits.

Security and privacy at every step

Your kit arrives in discreet packaging, your results are available on a private virtual dashboard, and your sample is stored in multiple locations for redundancy.

We’ve supported over 30,000 future parents

Trusted by top fertility experts, the US military, and people like you.

2024

Best Option for

Sperm Testing

& Freezing

It was super simple and my insurance covered it.

Austin

TRT patient

Legacy is a game changer in the male fertility space.

4.9

130+ Google Business reviews

Mail-in kits can be a simple way to screen for any underlying sperm problem. This is a great option if you are not comfortable taking a specimen to the lab.Stanton Honig, MD, Professor of Clinical Urology

This company has changed my life. I almost gave up on having a child... I got a rep the same day I reached out. He set everything up for me. HIGHLY RECOMMEND.

Quan

Verified client

I want the option for kids later

Freezing your sperm can help you have healthy children, whenever you’re ready.

Learn moreI want the option for kids later

I want to grow my family soon

Testing your sperm can help you conceive faster, identify issues that make conception difficult, and explore more fertility planning options.

Learn moreI want to grow my family soon

I want to understand my health

Sperm quality is a biomarker of your overall health. It can indicate a higher risk of heart disease, cancer, and even premature death.

Learn moreI want to understand my health

Unbox your fertility future

Modern sperm health starts with a simple at-home kit.

Don’t leave family to chance.